Plotting Liberation

A scheme for the Commons as Reparations

Maimuna TourayPartnership is giving, taking, learning, teaching, offering the greatest possible benefit while doing the least possible harm.

Partnership is mutualistic symbiosis. Partnership is life.

Any entity, any process that cannot or should not be resisted or avoided must somehow be partnered. Partner one another. Partner diverse communities. Partner life. Partner any world that is your home. Partner God. Only in partnership can we thrive, grow, Change. Only in partnership can we live.

—Octavia Butler, EARTHSEED: THE BOOKS OF THE LIVING, 1993

Octavia Butler went to the same high school as my mother. This is a fun fact I grew up hearing, usually following a quote like the one above from her travels deep into the Butler universe. I first read The Parable of the Sower when I was 19 years old, and it saw me; the book literally read me! I finished it in less than a day (I am an extremely slow reader btw) and it was then that I began to articulate the Commons as Reparations. While climate fires raged around our respective California homes, the book’s visionary protagonist Lauren Olamina wrote her first Earthseed verses and I wrote my first manifesto.That manifesto turned into another manifesto turned into a senior thesis turned into a zine turned into the digital book you’re about to read, and which you can download below and turn into a zine yourself!

The above verse on partnership found me recently, and it felt like another timely message from Octavia. The partnership that she outlines is one rooted in reciprocity (giving, taking), responsibility (learning, teaching), and repair (offering the greatest possible benefit while doing the least possible harm). This partnership is the commons: a social process that Black and Indigenous people have been practicing for time immemorial.

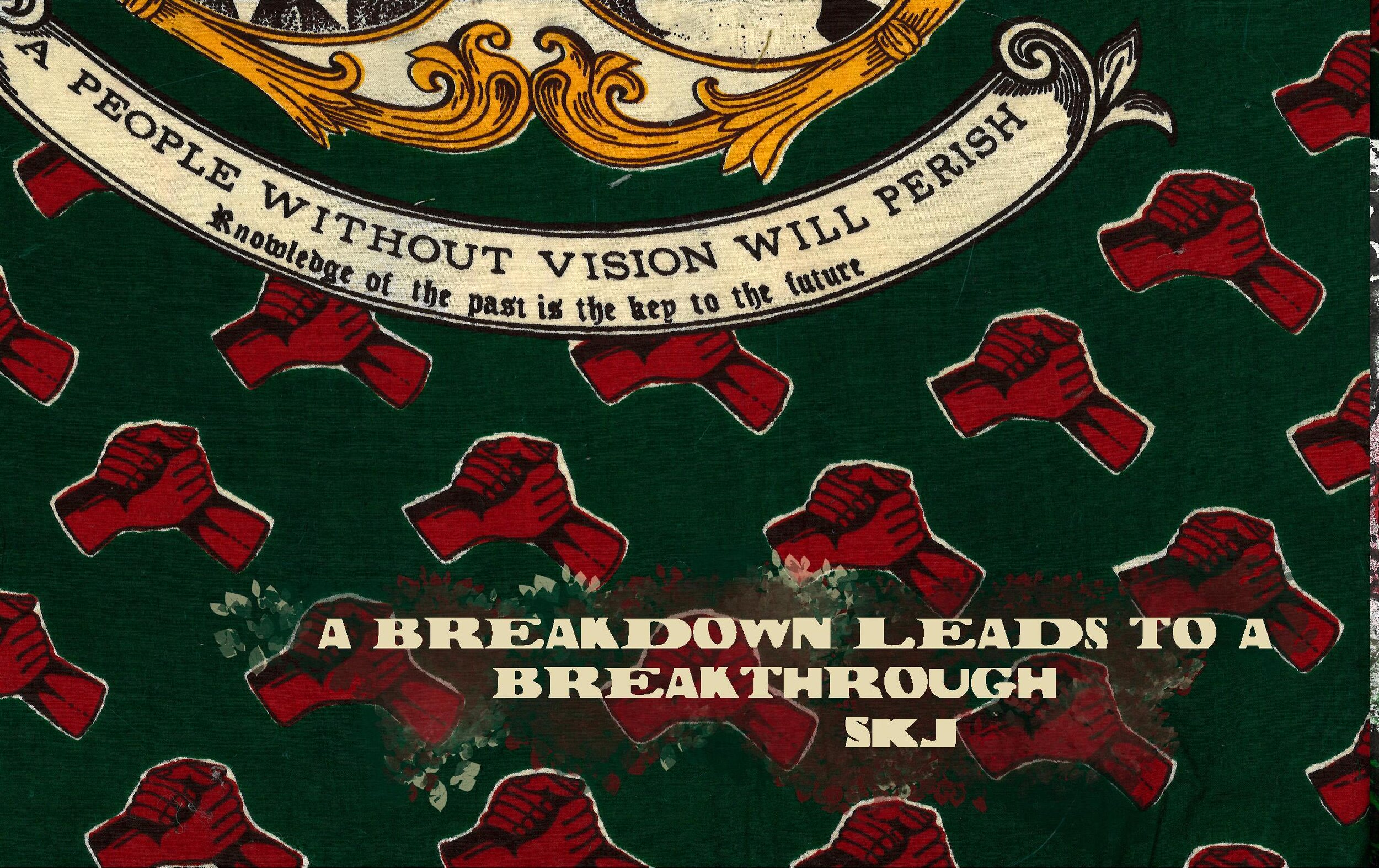

“Plotting Liberation: Commons as Reparations” envisions the commons as a form of reparations for the atrocities of slavery, settler colonialism, and their legacies of continued exploitation, violence, and destruction of our earth’s animate and inanimate communities. Published in the midst of climate catastrophe, and on the anniversary of the COVID-19 pandemic, this project acknowledges that we cannot separate slavery and settler colonialism from their contemporary consequences. So, I envision the commons as a social process where people share resources, decide how to govern themselves and those resources, and exist in common with the land and other-than human beings. This might look like the shared plots that slaves were forced to subsistence farm on, the beneficial societies of the antebellum period, free Black settlements, slums, cooperatives, community land trusts, and urban farms to name a few. My vision departs from reparations scholars like William Darrity and John Conyers who posit a form of reparations that is strictly monetary. Thinking instead with Octavia Butler, Silvia Federici, Angela Davis, Ta-Nehisi Coates, Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, JT Roane, Joanne Barker, and Mistinguette Smith, “Plotting Liberation” places the commons and reparations in conversation with each other while recalling a continued legacy of Black and Indigenous relationships to land. It argues for a specific form of “commoning” that places the human in common or, using Octavia’s teachings, in “partnership” with other-than human beings. I affirm that this commons radically repairs Black and Indigenous relationships—both to our bodies and to the land. Comparing the relationships that Black and Indigenous peoples have to land is evidence that the Commons as Reparations is a part of our entangled, radical ancestries.

The Black/Land Project (BLP) was founded in 2011 with the question “Why do Black people talk about their relationships to ‘the environment’ differently than people in mainstream environmental movements?” in mind. Gathering and analyzing stories about the relationship between Black people, land, and place, the project untangles this question in a series of interviews which—conducted between 2011 and 2013 in homes, farmyards, and urban gardens across the US—archive a Black relationship to land that directly challenges settler colonial relationships to property. One BLP interviewee, for example, tells the story of a creek that runs through the forest valley of his neighborhood:

All through my childhood this is where I’d go to play, to hide, or to pray in silence the way lonely children do… I had a very intimate relationship with the creek and woods in the valley, one that despite my young age, I now understand, was ancient in its nature. A few new people moved into the area, drawn by its beauty, and in the tradition of the suburban dream, trampled all over that beauty with gaudy uncreative architecture, hideous grass lawns, and infernal lamp posts that stay lit around the clock, alienating the nocturnal creatures they claim to love and marring the night sky. Regardless of my observations of their intrusion, I was dedicated to maintaining my relationship with the creek much like I had been, visiting her, cheering her up, bringing her gifts, telling her my stories and listening to hers…

One day, while visiting the creek, the interviewee heard the frantic calls of a woman screaming, “Get off my property!!”. They were perplexed, but quickly left. Recalling this moment, they share:

It seemed the most preposterous thing to me, that someone could claim ownership or dominion over nature like that, that someone would WANT to, disregarding nature’s role in our life as a guide and protector, an elder. Do you own your friends too? Your parent? Your dog? Do you own that rock over there? How about this cloud?... I now understand that it is this ancestral framework of relationship to, within, and of the land that allows some of us to see beyond settler colonial notions of property. The highest honor is not to claim ownership over land, but to be claimed by it.

The last sentence of this story sends chills down my spine. The highest honor is not to claim ownership over land, but to be claimed by it. Being claimed by land is a radical belonging, one that is at the core of the commons and also the power of its repair; not to claim land collectively but to be claimed by land collectively. In her 2018 essay “Decolonizing the Mind,” Lenape scholar, artist, and abolitionist Joanne Barker articulates a similar relationship to land. Offering an alternative to the European understanding of land as property, she writes:

What do I mean by “the land”? I do not mean the land in the terms of capitalism’s inheritable patrilineal estate, the terms of Marx’s property as an alienation from community, or the terms of the Left’s public commons. These lands are not Indigenous land. They belong to European and North American economics, histories, and politics, bound conceptually to patriarchal class hierarchies and their gendered and racial oppressions as well as to the resistance movements that have mobilized against them… Indigenous land is not property or a public commons… I claim and am claimed by Lenapehoking. But neither Lenapehoking, Oklahoma, nor Oakland are “my land.” [These lands] define me.

Drawing upon what I've learned from Butler, the Black/Land Project, and Barker, I propose the commons as a set of relationships to land that centers responsibility, care, and radical belonging. There is no one way to address the harm caused by settler colonialism and slavery: Black and Indigenous people have a long history of receiving broken contracts on behalf of white supremacist institutions. Former slaves were promised an acre and a mule of stolen land—a project of appeasement that, through a one-time “gift,” inducted the newly “freed” into a class of property-owning settlers. In other words, “repair” has been a concerted effort to mask genocide and undermine revolution, both sustaining the theft of land and lifeways and severing possibilities of solidarity.

Settler colonialism is a structure, not a single event; reparations rooted in offers of money or stolen land will never fully address the harms caused by the joint projects of anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity. The Commons as Reparations argues for restitution beyond one time payments, policies, or treaties. The Commons as Reparations is a recognition of the ongoing dispossession and desecration of our communities, both animate and inanimate. What does a repair look like that addresses the legacies of both slavery and settler colonialism? How do we manifest that vision into reality? Let’s begin with the Commons as Reparations.

Stroking coarse strands, she meditates on their union. Bone and flesh can give way to such calculated tenderness. One strand crosses underneath another, then over and under and over again. There is a sacred balance to this trio, an ancestral rhythm to this dance. Some decisions made out of fear can change the course of a century. The little Djembe player in her heart begins its solo. It plays a pattern so unnerving she stops braiding and places her left hand over her heart then her right hand on top of that. With pressure emanating through both palms, a prayer drips off her tongue shaped by overwhelming uncertainty. Some decisions made out of fear can change the course of a century. A warm breeze carrying the golden scent of the rice paddy lightly kisses her cheek. Spongy stems give way to spiky branches, she strokes the plant like a lover she’ll never greet again. Unable to say goodbye, she begins plucking the droopy strands of grain. Head high, eyes wide and determined, she knows in this moment the source of her strength. Tenderness returns to her fingertips this time to revise her work. She transforms her scalp into a sacred plot, her hair becoming fertile soil, and her fingers an ancient hoe. With each braid, she sows a lock of rice seeds in her hair, her own body a vessel for a liberatory future. She knows they will come for her, she knows she will never return to these lands, she knows that despite all this, she has secured a future in which those who come after her know radical love, hope, and care. Five centuries later, we remember her decision made out of fear.[1]

Growing up, my mother always said, “We’re spirit rich.” To me, this meant being surrounded by family, potlucks, hand-me-downs, and advice you weren’t always asking for. Growing up resource poor in Los Angeles, my grandmother grew legumes, tomatoes, squash, and green beans in our backyard and my mother possessed the ability to make a full meal out of scraps. At a very young age, I learned from my mother and grandmother how to be an architect of abundant worlds. I learned how to be adaptable, creative, and cooperative with the resources that were available to us. After the 2014 killing of unarmed teen Michael Brown, I designed youth discussions about bill H.R.40, which seeks to study reparations proposals to address the enduring effects of slavery in the United States.[2] We compiled our conversations into a film that we sent to government officials, including Barack Obama and former Michigan senator John Conyers who proposed the bill. I am now finding the language to connect the work I did in high school around reparations to the way I grew up commoning; this thesis is me sharing the seeds for that language.

The Plot in “Plotting Liberation” is inspired by J. T. Roane’s theorization in Plotting the Black Commons. The plot was a space for scheming liberation. “Taken together the various interlocking aspects of the plot erected a Black Commons whereby enslaved, free, and post-emancipation communities extended their notions of value that ran anathema to capitalist enclosure and mastery.”[3] The scheme/plot can then be understood as a commons where enslaved people shared knowledge and collectively decided how to prioritize the wellbeing of their communities, in addition to creating a place on the land they stewarded for the community to gather. This is the Commons as Reparations.

I refuse to distract from Indigenous demands for decolonization and repatriation of their lands, hence, this thesis critiques and complicates Black settlement and reparations in the United States. I will root my analysis of the Commons as Reparations in a continued legacy of Black and Indigenous relationships to land, arguing for a specific form of “commoning” that places the human in common with other-than-human beings. “Plotting Liberation: Commons as Reparations” affirms that commoning connects Black and Indigenous struggles and demonstrates how the commons, when intentionally articulated, can be a scheme/plot for our collective liberation. As Mistinguette Smith, founder of BLP, writes, “There is something in Blackness that knows property is a temporary agreement with the government, one easily revoked by the stroke of a pen or a calculating mob of white men with guns. Land, however, is something else. Land is something you know, and it knows you. Centuries of caring for land can bind people together with something stronger than shackles and deeper than freedom. Land, like blood, makes ties that cannot be unbound.”[4]

The production and extension of liberal property entails the conversion of a network of social relationships into a set of discrete bounded things.

The objects of property, in other words, become imagined as separate spaces.

—Nicholas Blomley, “Cuts, Flows, and the Geographies of Property,” 2011

Once the cut is made, the power to subjugate, dominate, and exploit the land and other-than-human beings becomes ordinately bestowed upon the settler colonizer, a granted “inheritance” as Morgensen writes.[5] As scholars Z. Amadahy and B. Lawrence maintain, “Probably the most fundamental principle of Indigenous cultures is human interdependence with other life-forms in non-hierarchical ways.”[6] The production of property cuts through these interdependent relationships, creating an individuated owner that is separate, indifferent, even hostile towards the living world around them. Property rights make cuts to the self, producing isolated individuals who belong only to the state and who are therefore only accountable to its eliminatory logics. The commons poses an intervention here by offering relationships that extend beyond these logics, creating dynamics where people belong to each other and the earth in interdependent networks.

I just want every home that I’m in to be full of love. By home of course I mean commons. I want every commons that I’m in to be full of love.

By commons I do mean a place full of love.

And by place I mean a belonging

I mean a house

I mean that spot under that tree

I mean that tree and the network of trees and beings that tree belongs to

I mean a body

My body

A place full of love

Would you say you move from a place full of love?

Would you say your body is full of love?

What would you say?

Lemme know

Can we imagine a world where we move from a place full of love as though our whole bodies were full up of it? Bubbling over and mixing up…

We remember the Black women who nestled rice seeds in their hair despite the great unknown that lay before them. We recall the Middle Passage and forget that so much more was transported than just bodies; profound knowledge and relationships to the land came with the people who were stolen from their homelands. The bond between Black and Indigenous people runs deeper than just the knowledge they shared during that time. It is reinforced by relationships to land that extend beyond white settler colonial conceptions of property. Relationships to land that place the human in common with land and other-than-human beings, what I argue is the commons.

The commons urges us to ask: If we maintain a relationship to land that is exploitative, how can our vision for freedom be truly liberatory? There is an interconnected relationship between the exploitation of the non-human and the exploitation of the Black human. We begin to see our actions not as radically individual but rather interconnected and interdependent with the earth. This reframes the nature of the exploitation of the earth. If we are ever to be free, we must free our relationships to the earth.

When I call for reparations, I do not call for a transfer in the ownership of the stolen land and bodies from the settler state to Black folk. I call for collective accountability and reciprocity between all people but explicitly Black and Indigenous people. When settler colonialism renders land into space, commons repairs through filling that space with responsible and reciprocal relationships. Repairs space into a place.

Judith Carney and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff. In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. University of California Press, 2009.H.R.40 - 116th Congress (2019-2020): Commission To Study And Develop Reparation Proposals For African-Americans Act.J. T. Roane. “Plotting the Black Commons.” Souls 20, no. 3, 2018.Mistinguette Smith. By Land Made Kin. Emergence Magazine, 2020.Scott Lauria Morgenson. "Spaces Between Us." Society and Space, 2012.Zainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence. “Indigenous Peoples and Black People in Canada: Settlers or Allies?.” Breaching The Colonial Contract, ed. Arlo Kempf; Springer, 2009.